Speciering—a term rooted in evolutionary biology—refers to the complex process through which new species form over time. Though the more common scientific term is speciation, “speciering” captures the same core idea: the gradual divergence of populations until they can no longer interbreed and produce fertile offspring. This transformation is one of the most fascinating phenomena in nature because it explains the extraordinary diversity of life on Earth. From the millions of insects in dense rainforests to the countless varieties of plants, birds, mammals, and microorganisms across the planet, speciering is the engine that drives biological variation.

Understanding speciering illuminates how life adapts, survives, and evolves. It is not merely a biological curiosity—it also holds practical implications for conservation, agriculture, medicine, and our global response to environmental change. This article explores the meaning, mechanisms, stages, drivers, and real-world relevance of speciering, offering a comprehensive view of how new species arise in an ever-changing world.

What Is Speciering?

At its core, speciering is the evolutionary process by which a single population splits into two or more distinct species. These new species become genetically unique, ecologically specialized, and reproductively separate. When scientists describe species as “reproductively isolated,” they mean that the populations cannot successfully interbreed any longer due to biological or behavioral barriers.

Speciering is not a sudden event. It unfolds over generations—sometimes thousands of years, sometimes millions. During this stretch of time, subtle genetic differences accumulate. Environmental pressures shape behavior, appearance, and reproductive strategies. Eventually, the populations diverge so deeply that they become distinct species.

Why Does Speciering Matter?

Studying speciering helps us answer fundamental questions:

-

How did life diversify from simple ancestors to the enormous biological richness we see today?

-

How do organisms adapt to changing environments?

-

Why do certain lineages split into many species while others remain relatively uniform?

-

How should conservationists protect species that are undergoing active divergence?

Speciering also gives insight into human evolution, crop domestication, antibiotic resistance, and the long-term effects of climate change. Without understanding species formation, we cannot fully grasp the past or plan for the biological future.

The Conditions Needed for Speciering

For a new species to form, one major condition must be met: reproductive isolation. This means individuals from two populations no longer mate with one another or cannot produce viable offspring. Reproductive isolation can arise from:

-

Physical separation (mountains, oceans, rivers)

-

Genetic or chromosomal differences

-

Behavioral changes (song, courtship, scent signals)

-

Ecological differences (diet, habitat, timing)

-

Evolutionary pressures that select for different traits

Once reproductive isolation takes hold, the path toward speciering accelerates.

Major Types of Speciering

Biologists generally categorize speciering into four primary types. Each mechanism highlights the creative power of evolution under different conditions.

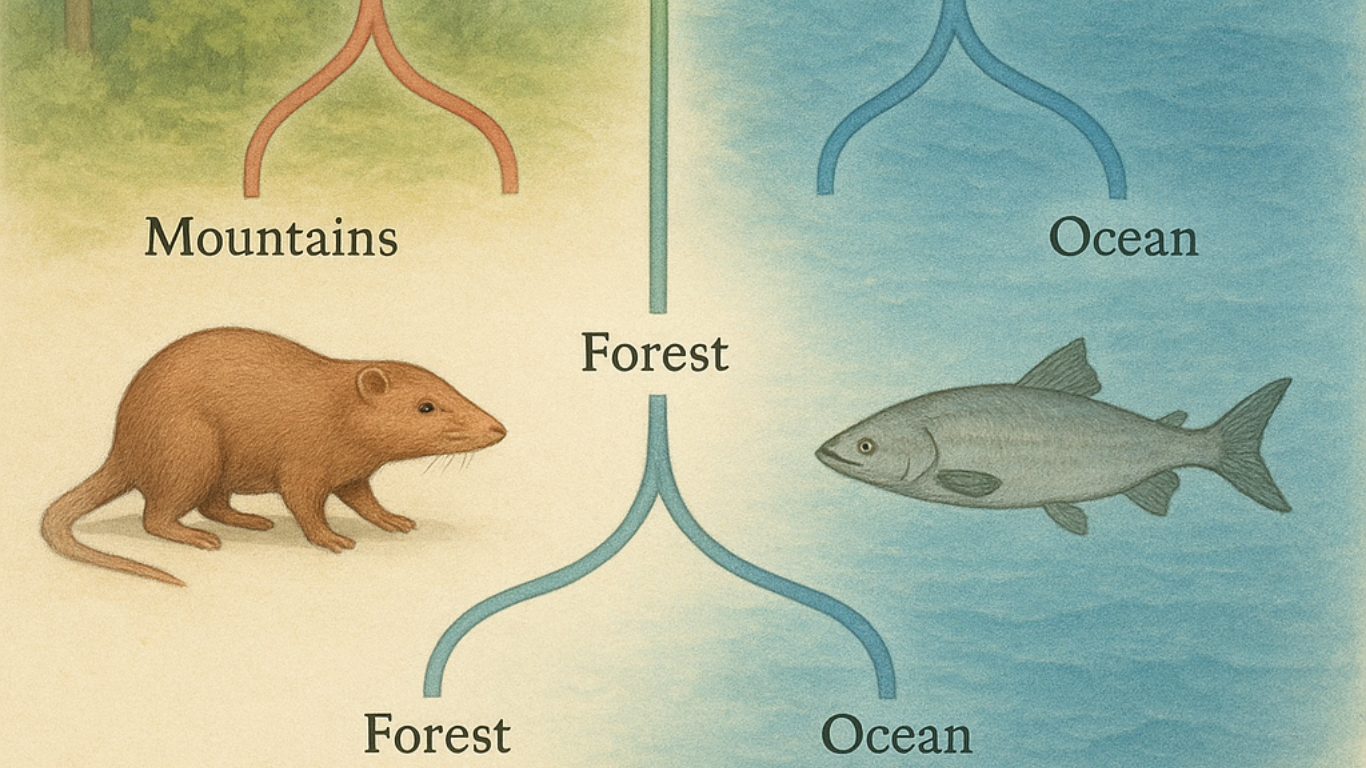

1. Allopatric Speciering (Geographic Speciation)

This is the most common form of species formation.

How it works:

A population becomes physically separated by a barrier such as:

-

A mountain range

-

A newly formed river

-

Continental drift

-

Climate changes that isolate habitats

-

Islands emerging from volcanic activity

Once separated, each group faces different environmental pressures. Over time, genetic changes accumulate independently, and the two populations adapt to their unique surroundings. Eventually, they become so different that they cannot interbreed.

Classic example:

Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands are a textbook case of allopatric speciering. Birds blown from one island to another evolved distinct beaks and behaviors depending on the local food sources.

2. Sympatric Speciering (Speciation Without Physical Barriers)

Sympatric speciering is more unusual because it occurs within the same geographic space.

It can occur through:

-

Genetic mutations that instantly create reproductive incompatibility

-

Changes in mating preferences

-

Polyploidy in plants (doubling of chromosome number)

-

Ecological specialization within the same region

Example:

Many plant species undergo polyploidy, instantly creating new species that can no longer breed with the original population.

3. Parapatric Speciering (Neighboring Populations)

In parapatric speciering, populations live adjacent to each other but experience different environmental conditions at the edges of their ranges. Limited gene flow plus strong environmental differences leads to divergence.

Example:

Grass populations living beside heavy-metal contaminated soils near mines evolved tolerance to toxic conditions. Over time, the tolerant and non-tolerant populations diverged to the point of becoming separate species.

4. Peripatric Speciering (A Small Group Breaks Off)

Peripatric speciering involves a small population breaking away from a larger one and evolving independently. Because small populations have fewer individuals, genetic drift plays a major role.

Example:

Flightless island birds often evolve through peripatric speciering when small founder populations settle on isolated islands.

Mechanisms That Drive Speciering

The emergence of new species is influenced by several evolutionary forces working simultaneously. These forces reshape populations across generations.

1. Natural Selection

Environmental pressures favor traits that improve survival and reproduction.

-

Predation encourages camouflage.

-

New food sources encourage changes in beak shape, jaw strength, or digestive systems.

-

Climate affects size, fur thickness, and behavior.

As selection pressures differ between populations, divergence deepens.

2. Genetic Drift

Random changes in gene frequencies—especially in small populations—can accelerate divergence. Over time, these random shifts create distinct genetic identities.

3. Mutation

Genetic mutations introduce new traits. Some are harmful, but many are neutral or beneficial. Mutations create the raw material for natural selection to shape.

4. Sexual Selection

Choosing mates based on specific traits (such as bright feathers, complex songs, or strong scents) can lead to rapid speciering. Over time, mate preferences isolate populations.

5. Environmental Change

Climate, food availability, soil chemistry, water conditions, and other ecological factors influence which traits succeed. Environmental variation fuels continuous evolutionary pressure.

The Stages of Speciering

While the process can differ across species, most speciering follows a general pattern:

1. Initial Isolation

A barrier—physical, ecological, behavioral, or genetic—creates separation.

2. Divergence

The isolated populations accumulate differences through natural selection, drift, mutation, and sexual selection.

3. Reinforcement

If the populations come back into contact, individuals may avoid mating with each other because hybrids have lower fitness. This strengthens reproductive boundaries.

4. Completion

Reproductive isolation becomes permanent, and the populations become distinct species.

Real-World Examples of Speciering

1. African Cichlid Fish

Hundreds of species in African lakes evolved in a relatively short period—driven by sexual selection, ecological niches, and environmental variation.

2. Apple Maggot Flies

Originally feeding on hawthorn trees, some flies switched to apples introduced by humans, eventually becoming reproductively isolated.

3. Ensatina Salamanders

A ring species around California’s Central Valley demonstrates how gradual variation around a geographic barrier can lead to reproductive isolation.

Speciering in the Modern World

Human activity accelerates environmental changes that affect speciering in multiple ways.

1. Habitat Fragmentation

Roads, cities, dams, and farmland divide ecosystems, isolating populations and sometimes promoting allopatric speciering.

2. Climate Change

As temperatures shift, species migrate to new regions. These movements can create new contact zones or isolate populations.

3. Invasive Species

Non-native organisms compete with local species, pushing them into new ecological roles that may promote divergence.

4. Pollution

Environmental stress—chemical, light, sound—can alter selection pressures and create new evolutionary pathways.

Why Understanding Speciering Is Crucial Today

-

Conservation Biology: Protecting species in the process of diverging helps maintain future biodiversity.

-

Agriculture: Plant breeders rely on speciering concepts to develop new, resilient crop varieties.

-

Medicine: Pathogens diversify rapidly; understanding speciering helps manage disease evolution.

-

Ecosystem Stability: Diverse ecosystems recover from disturbances more effectively.

Conclusion

Speciering is a fundamental process shaping the natural world. It explains how life continually diversifies, adapts, and evolves. Whether driven by physical separation, ecological shifts, genetic changes, or behavioral differences, speciering highlights the dynamic nature of evolution. As humanity shapes the planet more intensively than ever before, understanding how species form is crucial to protecting biodiversity, promoting sustainable development, and preparing for future environmental challenges.

Life’s story is one of constant change—and speciering is the mechanism that ensures that this story never stops unfolding.